Miscellaneous Linear Algebra Things

Published:

Some trivia found while teaching Linear Algebra in the Fall 2022 quarter.

Orthogonal set of Integer vectors

Consider the following sets of vectors:

\[\left\{\begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ 1 \\ 1 \end{bmatrix},\begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ -1 \\ 0 \end{bmatrix},\begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ 1 \\ -2 \end{bmatrix}\right\},\quad\left\{\begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ -2 \\ 1 \end{bmatrix},\begin{bmatrix} 2 \\ 1 \\ 0 \end{bmatrix},\begin{bmatrix} -1 \\ 2 \\ 5 \end{bmatrix}\right\}.\]These sets are orthogonal, and one can normalize them to make orthonormal bases (of $\mathbb{R}^3$). However, often the normalization involves many square roots that do not give a rational vector.

Of course some integer vectors do give rational vectors after normalization, like

\[\begin{bmatrix} \pm 1 \\ \pm 2 \\ \pm 2 \end{bmatrix},\begin{bmatrix}\pm 2 \\ \pm 3 \\ \pm 6 \end{bmatrix},\begin{bmatrix} \pm 1 \\ \pm 1 \\ \pm 1 \\ \pm 1 \end{bmatrix}.\]But as this corresponds to solving diophantine equations of the sort $x^2+y^2+z^2(+w^2)=n^2$, there are only a few examples with small numbers.

But one observes a bizarre pattern if one looks through these square roots. For the two examples above, normalizations give

\[\left\{\frac1{\sqrt{3}}\begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ 1 \\ 1 \end{bmatrix},\frac1{\sqrt{2}}\begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ -1 \\ 0 \end{bmatrix},\frac1{\sqrt{6}}\begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ 1 \\ -2 \end{bmatrix}\right\},\quad\left\{\frac1{\sqrt{6}}\begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ -2 \\ 1 \end{bmatrix},\frac1{\sqrt{5}}\begin{bmatrix} 2 \\ 1 \\ 0 \end{bmatrix},\frac1{\sqrt{30}}\begin{bmatrix} -1 \\ 2 \\ 5 \end{bmatrix}\right\}.\]Observe that $\sqrt{3}\cdot\sqrt{2}\cdot\sqrt{6}=6$ and $\sqrt{6}\cdot\sqrt{5}\cdot\sqrt{30}=30$; the products of norms are integers! This tells that norms of an orthogonal set of integral vectors are not just random square roots, but rather have a pattern on their own.

I formulate this as follows.

Proposition. Let $\mathbf{v}_1,\mathbf{v}_2,\ldots,\mathbf{v}_n\in\mathbb{Z}^n$ be integral nonzero vectors. Suppose they are orthogonal, i.e., $\langle\mathbf{v}_i,\mathbf{v}_j\rangle=0$ if $i\neq j$. Then the product of their Euclidean (i.e., $\ell^2$) norms are integer, i.e., \(\vert\mathbf{v}_1\vert\cdot\vert\mathbf{v}_2\vert\cdots\vert\mathbf{v}_n\vert\in\mathbb{Z}\).

The only proof that I know uses Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) in its essential step.

(Proof) Think of each $\mathbf{v}_i$ as column vectors. Let $P=\begin{bmatrix}\mathbf{v}_1 & \mathbf{v}_2 & \cdots & \mathbf{v}_n \end{bmatrix}$ be the $n\times n$ matrix whose columns are given vectors. Then because

\[P^\dagger P = \begin{bmatrix} \vert\mathbf{v}_1\vert^2 & 0 & \cdots & 0 \\ 0 & \vert\mathbf{v}_2\vert^2 & \cdots & 0 \\ \vdots & \vdots & & \vdots \\ 0 & 0 & \cdots & \vert\mathbf{v}_n\vert^2 \end{bmatrix} \label{eqn:1}\]is a diagonal matrix, we have a SVD of the matrix P as

\[P = U\Sigma V^\dagger,\]where $V=I$ is the identity matrix and

\[\Sigma = \begin{bmatrix} \vert\mathbf{v}_1\vert & 0 & \cdots & 0 \\ 0 & \vert\mathbf{v}_2\vert & \cdots & 0 \\ \vdots & \vdots & & \vdots \\ 0 & 0 & \cdots & \vert\mathbf{v}_n\vert \end{bmatrix}\]is the diagonal matrix of norms. Because $U$ is an orthogonal matrix, we have $\det U=\pm 1$. Therefore,

\[\det P = (\det U)(\det\Sigma)=\pm\prod_{i=1}^n\vert\mathbf{v}_i\vert \label{eqn:2}\]is an integer, as P is an integral matrix. $\square$

Of course, there is a shorter proof, by observing that \eqref{eqn:1} gives $\det(P^\dagger P)=(\det P)^2=\prod_i\vert\mathbf{v}_i\vert^2$, which gives \eqref{eqn:2}. The proof stated above is intended to show how SVD is involved. Having said so, I wonder if Proposition above has purely number-theoretical proof.

Eigenvalues of $3\times 3$ matrices

Consider the problem of finding eigenvalues of a square matrix. For $2\times 2$ matrices, instead of computing the characteristic polynomial as

\[\begin{vmatrix} \lambda-a & -b \\ -c & \lambda-d \end{vmatrix} = (\lambda-a)(\lambda-d)-(-b)(-c),\]we have much less effort to find the trace and determinant of the matrix and attempt to solve

\[\lambda_1+\lambda_2=a+d,\quad \lambda_1\lambda_2=ad-bc.\label{eqn:3}\]But even for $3\times 3$ matrices, trace and determinant are not everything. The situation is not that desperate: traces of powers of the matrix is known to be good replacements, as supported by the following fact

\[\sum_{i=1}^n\lambda_i^k = \mathrm{trace}(A^k),\]where $A$ is an $n\times n$ matrix, and $\lambda_1,\ldots,\lambda_n$ are eigenvalues of A counted with algebraic multiplicities, and $k\geq 0$ is any integer.

One can assemble this to develop systems like \eqref{eqn:3} above. For instance, if $A$ is $3\times 3$, then we have

\[\lambda_1+\lambda_2+\lambda_3=\mathrm{trace}(A), \\ \lambda_1\lambda_2+\lambda_2\lambda_3+\lambda_3\lambda_1=\frac12(\mathrm{trace}(A)^2-\mathrm{trace}(A^2)), \\ \lambda_1\lambda_2\lambda_3=\frac16\left(2\,\mathrm{trace}(A^3)-\mathrm{trace}(A)\cdot(3\,\mathrm{trace}(A^2)-\mathrm{trace}(A)^2)\right),\]where the last line is a complicated way of saying $\lambda_1\lambda_2\lambda_3=\det A$. (See Wikipedia for a more general formula.)

It feels odd to see that the degree 2 elementary symmetric polynomial $\lambda_1\lambda_2+\lambda_2\lambda_3+\lambda_3\lambda_1$ is having a somewhat complicated formula (modulo trace and determinant). It turns out that this formula can be simplified, with the cost of having a new ‘determinant-like formula.’ as sketched below.

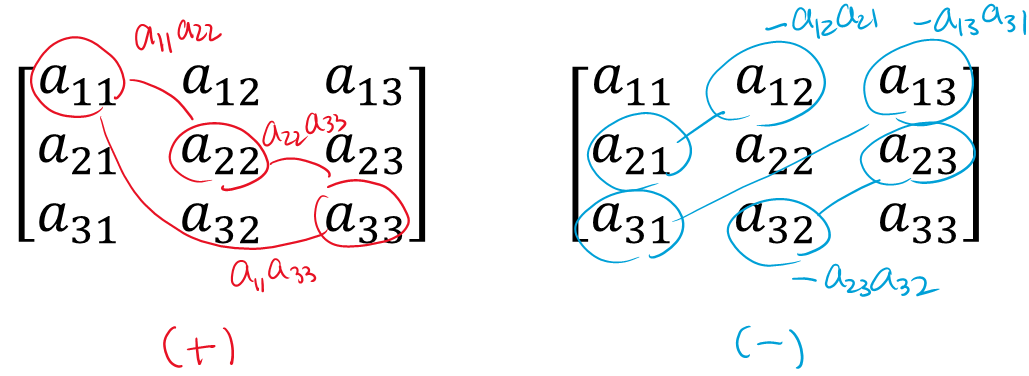

Denote the entries of $A=(a_{ij})_{1\leq i,j\leq 3}$. Then

\[\mathrm{trace}(A)^2-\mathrm{trace}(A^2) = (a_{11}+a_{22}+a_{33})^2 \\ - (a_{11}^2+a_{12}a_{21}+a_{13}a_{31}) \\ - (a_{21}a_{12}+a_{22}^2+a_{23}a_{32}) \\ - (a_{31}a_{13}+a_{32}a_{23}+a_{33}^2) \\ = (a_{11}^2+a_{22}^2+a_{33}^2)+2(a_{11}a_{22}+a_{22}a_{33}+a_{33}a_{11}) \\ - (a_{11}^2+a_{22}^2+a_{33}^2)-2(a_{12}a_{21}+a_{13}a_{31}+a_{23}a_{32}) \\ = 2\left[a_{11}a_{22}+a_{22}a_{33}+a_{33}a_{11}-a_{12}a_{21}-a_{13}a_{31}-a_{23}a_{32}\right]\]gives

\[\lambda_1\lambda_2+\lambda_2\lambda_3+\lambda_3\lambda_1= \\ = a_{11}a_{22}+a_{22}a_{33}+a_{33}a_{11}-a_{12}a_{21}-a_{13}a_{31}-a_{23}a_{32}.\]

I will temporarily call this the 2-block determinant-trace. (This is also known to be the trace of the adjugate matrix.)

Example. Consider the $3\times 3$ matrix

\[\begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 & -1 \\ 0 & 1 & 2 \\ -1 & 2 & 5 \end{bmatrix}.\]Then the trace of this is 7, the determinant is 0 ((row 3)=2.(row 2)-(row 1)), and the 2-block determinant-trace is $1\cdot 1 + 1\cdot 5 + 1\cdot 5 - (0\cdot 0 + (-1)\cdot(-1) + 2\cdot 2) = 11-5=6$. This leads us to solve

\[\lambda_1+\lambda_2+\lambda_3=7, \\ \lambda_1\lambda_2+\lambda_2\lambda_3+\lambda_3\lambda_1=6, \\ \lambda_1\lambda_2\lambda_3=0.\]At least one of the eigenvalues is 0, say $\lambda_3=0$, so we deal with the usual quadratic question $\lambda_1+\lambda_2=7$ and $\lambda_1\lambda_2=6$. It turns out that $\lambda_1=6,\lambda_2=1$ are the remaining eigenvalues.

It is not hard to generalize the computation above, and show that

\[\sum_{i<j}\lambda_i\lambda_j = \sum_{i<j}(a_{ii}a_{jj}-a_{ij}a_{ji}),\]for $n\times n$ matrices. On the other hand, the trace of the adjugate matrix is

\[\mathrm{trace}(\mathrm{Adj}(A)) = (\det A)\cdot\sum_i\frac1{\lambda_i},\]so two matches only when $n=3$.

Update Log

- 230128: Created

- 230226: Added some sentences regarding adjugate matrices